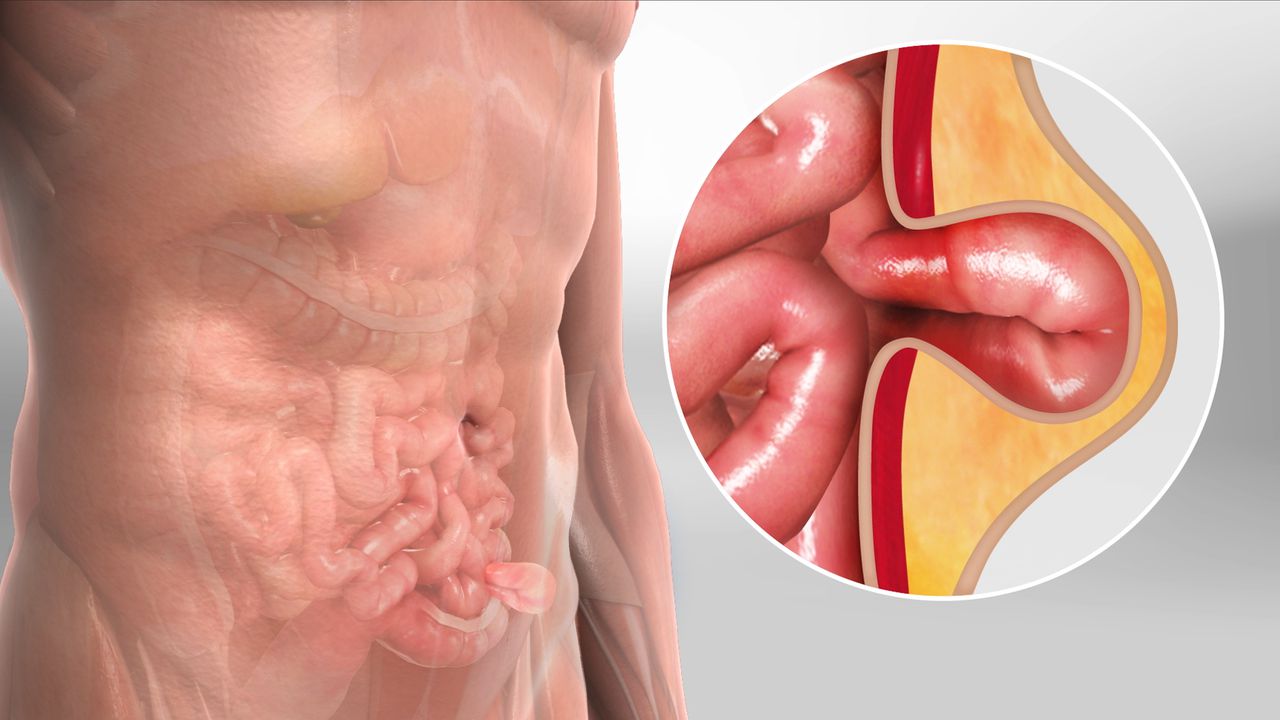

The appearance of a hernia, that peculiar sensation of tissue or an organ pressing through a weakened point in the surrounding muscle or fascia, usually marks the beginning of a specific and necessary medical journey. While a few smaller hernias might be managed with watchful waiting, most progress to a point where surgical intervention, or hernioplasty, becomes the definitive treatment. The decision to pursue surgery is rarely straightforward for the patient, involving not just the physical discomfort and risk of complications like incarceration or strangulation, but also navigating the complexities of surgical options, recovery expectations, and the lingering uncertainties about long-term recurrence. Understanding this process, from the various classifications of the defect to the nuances of repair techniques, is essential for anyone facing this common diagnosis.

Understanding this process, from the various classifications of the defect to the nuances of repair techniques, is essential for anyone facing this common diagnosis.

The sheer variety of hernia presentations makes the initial diagnosis more than a simple identification of a bulge. Inguinal hernias, which predominantly affect the groin area and account for the vast majority of cases, are subdivided into direct and indirect types, the distinction being the anatomical path they take through the abdominal wall, a detail that holds significance for the chosen repair strategy. Further categories include femoral hernias, which are more common in women and pose a higher risk of becoming trapped; umbilical hernias, occurring at the navel; and incisional or ventral hernias, which develop at the site of a previous surgical incision where the tissue has failed to heal with sufficient strength. Each type presents a unique challenge to the surgeon, necessitating a repair tailored not just to the patient’s overall health profile, but also to the exact location and size of the defect in the fascial layers.

The sheer variety of hernia presentations makes the initial diagnosis more than a simple identification of a bulge.

Once the specific type of hernia is identified, the discussion moves to the method of repair, a decision largely framed by the surgeon’s experience, the patient’s health, and the physical characteristics of the hernia itself. Historically, the open or traditional approach, often involving a single, sizable incision directly over the hernia, was the default. This method allows the surgeon a direct view to reduce the herniated tissue back into the abdominal cavity and then reinforce the weakened wall. Modern practice, however, increasingly offers minimally invasive options, primarily laparoscopic and, in some settings, robotic-assisted repair. These techniques utilize several small keyhole incisions, through which specialized instruments and a camera are introduced, allowing the repair to be performed from within the abdominal cavity. Comparing these approaches involves a complex trade-off between the perceived benefits of reduced incision size and post-operative pain associated with the laparoscopic method, against the relative simplicity, lower cost, and ability to use regional anesthesia for the open technique.

Modern practice, however, increasingly offers minimally invasive options, primarily laparoscopic and, in some settings, robotic-assisted repair.

The contemporary landscape of hernia surgery is dominated by the concept of ‘tension-free’ repair, a principle almost universally achieved through the use of surgical mesh. The rationale for mesh implantation is rooted in the recognition that hernias develop due to an inherent weakness in the connective tissue; simply stitching the native, compromised tissue back together often creates tension on the repair site, leading to high recurrence rates. Mesh—a sterile, screen-like material—is deployed to bridge the defect or to reinforce the weakened area, acting as a scaffold that encourages the patient’s own tissue to grow into it, creating a stronger, more durable repair that avoids excessive tension. These materials vary considerably, from permanent synthetic polymers like polypropylene to temporary, absorbable meshes that dissolve as the body generates its own scar tissue.

The contemporary landscape of hernia surgery is dominated by the concept of ‘tension-free’ repair, a principle almost universally achieved through the use of surgical mesh.

Despite its widespread acceptance and documented success in reducing recurrence, the use of mesh carries a small but significant array of potential complications that patients must be aware of. While rare, adverse outcomes can include chronic pain, which may result from nerve entrapment or persistent inflammation around the mesh; infection of the mesh itself, which can be difficult to treat and sometimes necessitates removal; or, in extremely rare cases, erosion of the mesh into adjacent organs like the bowel or bladder, particularly in repairs done from the inner abdominal wall. Discussion surrounding mesh complications often becomes simplified in public discourse, but the reality is that for the vast majority of patients and hernia types, the benefit of reduced recurrence risk provided by mesh far outweighs the potential complications, a balance that is consistently supported by current surgical society guidelines.

While rare, adverse outcomes can include chronic pain, which may result from nerve entrapment or persistent inflammation around the mesh.

Preparing for a hernioplasty involves more than just the logistical arrangements for the day of surgery. Preoperative optimization, where applicable, is a critical, often neglected factor that significantly influences the outcome. For instance, smoking cessation for at least a few weeks prior to the procedure has been strongly linked to lower rates of wound complications and recurrence, as nicotine impairs blood flow and the body’s healing capacity. Similarly, managing chronic conditions like diabetes to ensure blood glucose levels are tightly controlled minimizes the risk of infection and promotes better wound healing. Surgeons may also advise a period of physical conditioning or weight management, as the mechanical stress on the repair is directly proportional to the patient’s body mass and physical activity. Adherence to strict fasting guidelines is also mandatory to prevent the serious, though rare, complication of aspiration during the administration of general anesthesia.

Preoperative optimization, where applicable, is a critical, often neglected factor that significantly influences the outcome.

The immediate post-operative period is characterized by the management of pain and the slow, deliberate return to normal function. Pain management is tailored to the individual and the technique used, with laparoscopic repairs often requiring less narcotic pain medication due to the smaller degree of muscle disruption. Patients are encouraged to move gently as soon as possible, often within hours of the procedure, as walking aids in circulation, helping to prevent blood clots and pulmonary complications. However, restrictions on lifting, pushing, or pulling anything heavier than a few pounds are critically important and must be strictly adhered to for a period usually lasting four to six weeks. Ignoring these restrictions, even briefly, places undue strain on the fresh repair site and dramatically increases the risk of recurrence before the mesh has fully integrated and scar tissue has adequately formed.

The immediate post-operative period is characterized by the management of pain and the slow, deliberate return to normal function.

Constipation is a common and particularly troublesome side effect in the early recovery phase, often caused by the combined effects of anesthetic agents, temporary inactivity, and prescribed pain medication. Straining during a bowel movement dramatically increases intra-abdominal pressure, which can directly threaten the integrity of the surgical repair. Therefore, post-operative care plans routinely emphasize high-fiber diets and the use of stool softeners or laxatives to ensure effortless bowel movements. Maintaining adequate hydration is also fundamental, supporting not only gastrointestinal function but also overall tissue healing and the clearance of residual anesthetic from the system.

Constipation is a common and particularly troublesome side effect in the early recovery phase, often caused by the combined effects of anesthetic agents, temporary inactivity, and prescribed pain medication.

Long-term recovery and the measure of success are fundamentally tied to the prevention of recurrence and the avoidance of chronic pain. While the initial return to light activities is rapid, the true, durable strength of the repair takes months to fully mature. Surgeons advise a gradual, supervised return to strenuous exercise and heavy lifting, ensuring the abdominal wall has the necessary time to fully incorporate the mesh and establish a stable, reinforced layer. Chronic post-herniorrhaphy pain, while uncommon, is an outcome that can significantly impact quality of life, and its management often requires a multidisciplinary approach, including nerve blocks, physical therapy, and pain specialists, underscoring the necessity of selecting a technique and a surgeon who prioritize nerve preservation during the initial operation.

Long-term recovery and the measure of success are fundamentally tied to the prevention of recurrence and the avoidance of chronic pain.

Navigating the necessary procedure requires a solid understanding of the various options and the nuanced risks involved. Patients must engage in detailed conversations with their surgical team, asking specific questions about the type of hernia, the rationale for the chosen technique (open versus minimally invasive), the material and placement of any mesh, and a realistic, detailed breakdown of the expected recovery timeline and activity restrictions. Recognizing that hernia surgery is not a minor procedure but a significant reconstruction of a core structural element of the body fosters the necessary diligence during the recovery period, which is ultimately the final, critical determinant of long-term success.

Recognizing that hernia surgery is not a minor procedure but a significant reconstruction of a core structural element of the body fosters the necessary diligence during the recovery period.

Hernia repair requires detailed preoperative diligence and strict post-operative adherence to restrictions for a tension-free structural success and a durable outcome.